Lipidomics of bacteria, and unsaturated fatty acid production in Streptcococci

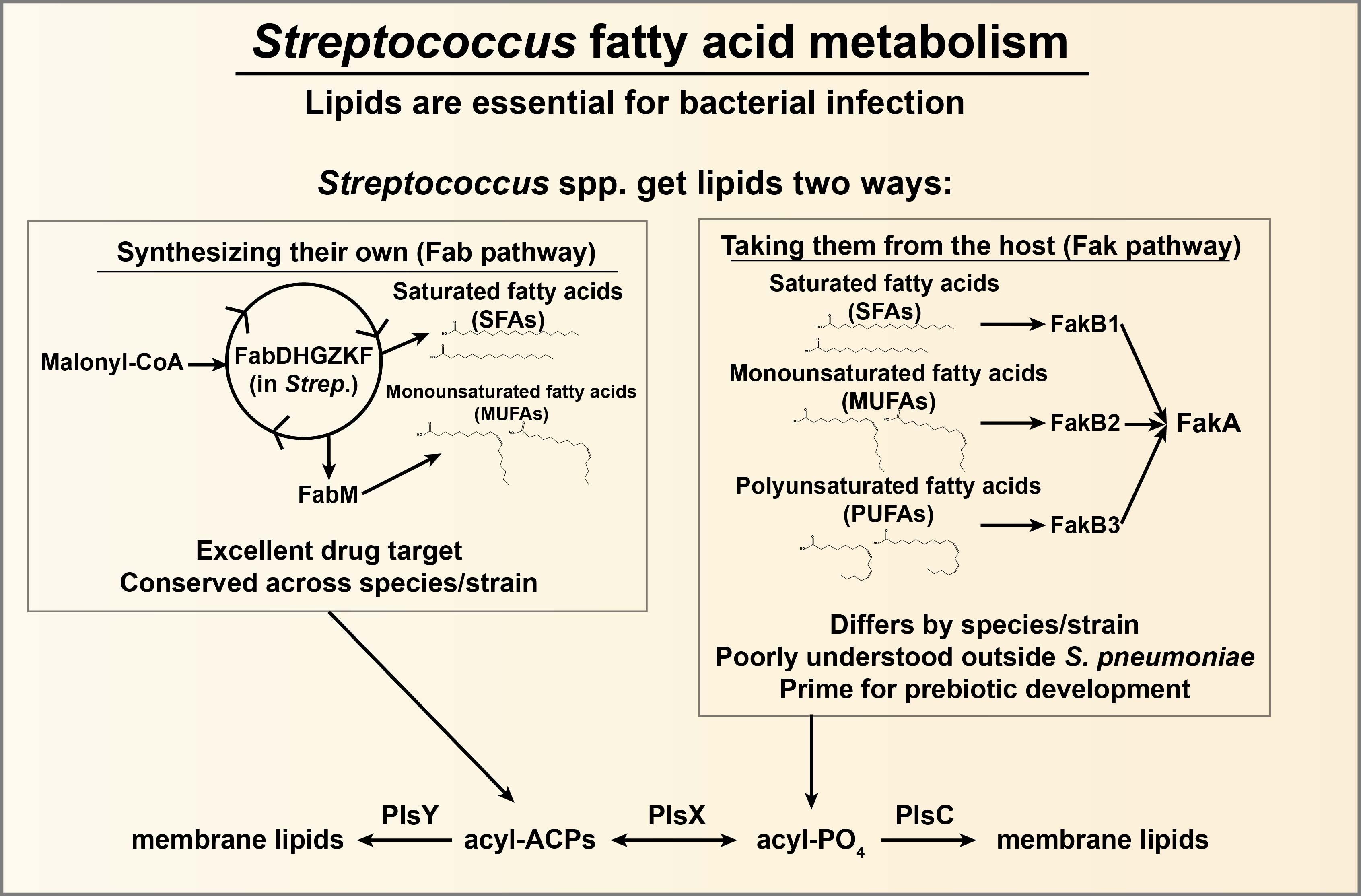

The antibiotic resistance crisis is a looming global health threat, with deaths due to antimicrobial resistant pathogens predicted to increase to nearly 10 million per year worldwide, and possibly become the #1 cause of human mortality by 2050 if no action is taken. Along with increased antibiotic stewardship and vaccine development, the development of novel therapeutics (including prebiotics and antibiotics) is an important step to secure the future from this threat. The bacterial genus Streptococcus contains some of the most important pathogens and commensals of the human microbiome, with multiple species causing significant human morbidity and mortality. Streptococcus spp. obtain fatty acids by either synthesizing them de novo through the fatty acid biosynthesis (Fab) pathway or acquiring them from the environment through the fatty acid kinase (Fak) pathway. Although the Fab pathway was explored as an attractive drug target, this approach is vexed by the ability of Streptococcus to bypass this using exogenous fatty acids via the Fak pathway. Our preliminary data indicates that: 1) there are taxa-to-taxa differences in the ability of various Streptococcus to utilize exogenous fatty acids via the Fak pathway, 2) novel genes are involved in the process, and 3) specific exogenous fatty acids inhibit ComCDE signaling. These features could likely be exploited by using specific fatty acids as prebiotics to prevent disease, as was recently demonstrated with Lactobacillus spp. and bacterial vaginosis. However, we lack a comprehensive understanding of the ability of Streptococcus spp. to acquire and remodel host fatty acids, hindering the discovery of therapeutic prebiotic and antibiotic approaches. Our hypothesis is that Streptococcus spp. possess distinct abilities to utilize and remodel host fatty acids, and that these fatty acid pathways directly influence ComCDE-dependent signaling and virulence gene expression. The project currently has these short-term goals: 1) Define the genotype–phenotype relationships between FakB isoforms and host fatty acid utilization and modification in Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Streptococcus pneumoniae, 2) Determine the role of the host fatty acid-responsive genes ohyA1, ohyA2, and SMU.2133 in Streptococcus mutans fatty acid metabolism, and 3) Determine the effect of exogenous fatty acids on Streptococcal competence and downstream virulence factors. Overall, this project will reveal how three different important Streptococcus pathogens utilize and modify host fatty acids and discover how this process integrates with quorum-sensing and virulence regulation. By defining the biochemical and signaling pathways connecting fatty acid utilization to pathogenic behavior, this work will uncover new molecular targets for prebiotic strategies that disarm pathogens.

This project is funded in part by NIH/NIDCR R00-DE029228.